The renowned design magazine Abitare dedicated the cover to him. Born in 77, from Palermo, Francesco Librizzi chose to launch his studio and product design in Milan in 2005, but the bond with his birthplace is strong and indissoluble. Coming and going from the big city full of stimulus to the places of his island, where his father and uncle made him discover his tendencies since he was a child, which are creating, handling and transforming to give life to new items and spaces. His work won prestigious awards – among which the Prix Émile Hermès and the honourable mention for the extension of the Loris Malaguzzi centre in Reggio Emilia – and was exhibited by institutions, such as the Louvre and the Triennial of Milan. Among the most significant set ups are the project of the Italian Pavilion at the 12th Biennial of Architecture in Venice in 2010, and the Bahrein Pavilion at the 13th edition held in 2012. In 2013, he was invited to design an installation dedicated to Bruno Munari in occasion of the 6th edition of the Design Museum Triennial.

“Being able to design is not a question of expertise, but rather of aptitudes”. Where does this awareness come from?

It’s an egalitarian thought basing work on competences: everyone can acquire it making an effort. However, equality is not the best possible form of democracy. It has the defect of placing rights before possibilities. Attitude comes from talent. It doesn’t require strain, but abandon. Competences need an a priori choice on the long path one wants to follow. They are based on selection. On the contrary, the talent form everybody has in a different way cannot be chosen. It can be recognized. In the end, I believe in democracy made of people that are different from each other, where everyone follows his/her own attitudes, rather than achieving some skills with effort. I think that a society based on fulfilment rather than sacrifice is more natural.

In an interview to Domus, you stated that your passion or “attitude” for design has roots in your childhood and birthplace, that is Sicily.

Sicily is a triumph of forms. I was and still are very lucky to be born here. A “Sicilian” has a deeply dramatic imaginary, a well-structured sense of narration, an atavic nature to dialectal thought. Acuity, enlightenment, irony and taste are features I recognize in very many Sicilians. All this beauty is also violence. Distancing yourself can sometimes help to avoid being burnt. Milan is a civil, informal, serene city. Citizens can do their work in a natural way and with much self-respect. It’s a wonderful place to work, live, meet the great people that are still based here.

A staircase seen as cornerstone and “tool to describe a triumph of panoramas and landscapes”. How do steps and handrails become essential in a project?

A staircase is a great architectural occasion. It is both summary and excess of space. It’s a formal, sublime and absolutely real moment, but transient at the same time: it literally is the exit from space and way to a higher level. With the project of some staircases, we searched for the essence of space and managed to domesticate it.

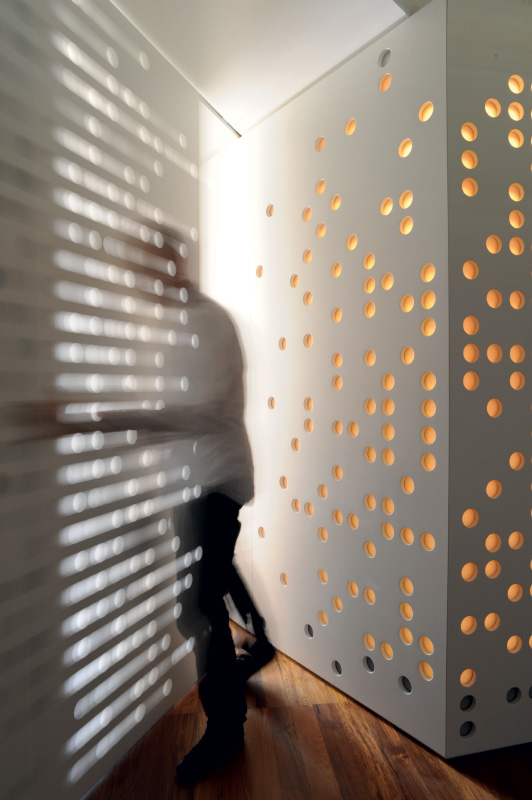

Tectonics of spaces comes out in many of your projects, as if everything had to be observed and experienced from on high. Where does this vision come from?

Space doesn’t exist, but can be built. Every author tries to find a match between words and ideas. In other words, searching for a language that expresses what the author sees and wants to pass on to the others. When I started to work on spatial structures including volume, even if they didn’t have mass, it was a real discovery. My language took shape and turned into a very specific point of view, which I called “Maximum Visibility” since then.

Which project thrilled you most?

It’s strange that the projects we work hard on are not necessarily the best ones. The most successful ones were those I did with such simplicity that I nearly achieved indifference. For example, the first staircase, which the public really appreciated a lot, was an absolutely spontaneous project for me: I didn’t imagine I had done something important until the recognitions from magazines and from the public of colleagues and passionate people. The project for the roof-tip restaurant at the Triennial and the project for the Bahrein Pavilion at Expo 2015 marked a great path in my studio.

How important is it for a young designer to become member of Adi Sicilia, and what kind of didactic tasks do you carry out on our island?

Joining an institution like ADI means being part of the game. Above all in a region like Sicily, often far away and excluded, feeling like being part of the great and continuous tradition of Italian design can be essential for a young designer. I remember that I saw Enzo Mari walking along the roads when I arrived in Milan waiting at a traffic light on my motorbike. I was astonished: it was really him in the flesh. Years after we worked together. So it was all real. I think that being part of ADI can give you the same sense of continuousness and possibilities. I’ve been lucky I had great teachers. A teacher is he who passes a basic thing on to you, which is able to have the effect of a big change in your life. I teach to repay that debt. In Sicily, I hope that my contribute can increase the good possibilities of young people in our island

Recommended song for the reading of the present article: Architetture lontane – Paolo Conte